A post about affect-production, concept-production, and the suggestive realm.

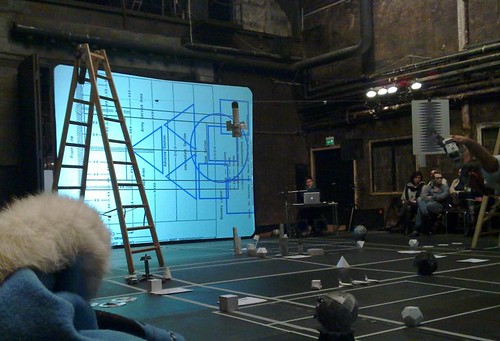

A couple of days ago, I watched BADco perform ”The league of time” in Stockholm. I’d seen it once before, a little more than a year ago, in Skegness, as a part of Intercult’s Black-North Seas project. Since I first saw the production, I had tried to capture and convey what it was that I saw in Skegness. Or, more specifically, I had tried to convey an experience, a feeling, a sentiment, a sensibility. Ironically, even after seeing it a second time, I could not really capture what it is that the performance does, and why it works so well. The only words I could produce was ”suggestive, no?”.

OK – so ”The league of time” produces something in me. This something cannot be reduced to a simple statement like ”character X was not very credible” or ”I think that the show is spot on in its rendering of the sentiments of pre-Stalin USSR”. If pressed, I would say that the performance has produced a certain sensibility for futurist dreams. It has made me somewhat more capable of being thrilled by the thought of something radically different that awaits us. I could go on forever here, not really capturing this feeling, but let’s just say that the performance has tickled, and possibly sensitised one or several nerves in me – nerves that were previously either dormant or suppressed.

Here, we can connect to Vinciane Despret’s thoughts about body and affect – to have a body is to learn to be affected, to learn to be moved by other bodies. Bruno Latour has adapted Despret’s point, stating that learning to be affected implies becoming more articulate: Just as the ”noses” in the Paris perfume industry learn to detect and be moved by certain scents, I have learnt to become be moved by futurist dreams, constructivist compositions, and so forth.

This then, is one way of understanding what it means to speak of art as the production of affects, as discussed in the previous post. It also connects nicely to Julian Schabel’s statement regarding his paintings of big wave surfing – that the pieces are ”not about the images, but ”¦ about how you feel when you are standing in front of it”. Two points can be made here:

1. As we see now, to speak of affect is not to speak of art as something meant to ”provoke” or ”stir up emotion”, but to generate new capacities. As Brian Massumi writes in the introduction to A Thousand Plateaus:

The question is not: is it true? But: does it work? What new thoughts does it make it possible to think? What new emotions does it make it possible to feel? What new sensations and perceptions does it open in the body?

2. To speak of art in this way leads the discussion away from deconstruction. Schabel does not ask us is not to decipher the image, but to experience his painting. Can his work actually make you ”feel how you feel when you are actually surfing, or when you are drowning”? Probably not, but the point here is to go a bit easy on the deconstructing. Ironically, in the current exhibition at Art Gallery of Ontario, the curator has chosen to do a bit of both – pointing to what surfing supposedly symbolises or represents.

Back to ”The league of time”: So, the performance has made me capable of feeling something I haven’t felt before. Possibly, it has also made me capable of thinking thoughts that I have not thought before. (Indeed, there is a bit of futurism in the manuscript for the little publication that I am working on now.) Strictly speaking, these are two different activities – the production of affects (art), and the production of concepts (philosophy). Nevertheless, in the context of BADco’s performance, it is hard to separate these two forms of production. (Note how Massumi, in the quote above, bundle them up.)

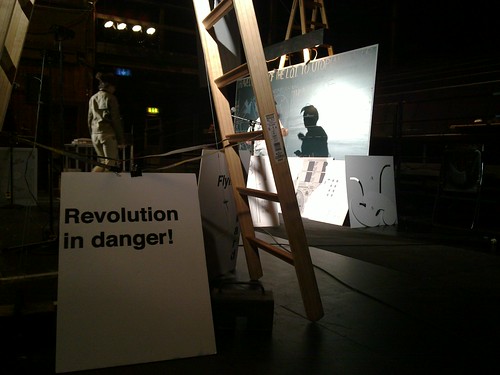

This theme – the relation between art and philosophy, theory and performance – was discussed during the artist talk that followed the Stockholm performance. When asked whether the production is ”theoretical”, Goran Sergej Pristas of BADco outlined some of the sources of inspiration: Mayakovsky’s poem ”The flying proletarian”, Kafka’s America, The Factory of the Excentric Actor and it’s connections to Chaplin and American slapstick, King Kong and the Empire State Building, the Man-Machine and Henry Ford, Július Koller. The retort – is it not, then, ”a tad theoretical”? – the artist talk ended up becoming a discussion on the potential merits of theory.

Unfortunately, the talk never touched upon the affect-producing aspects of the performance. Does BADco, like Schnabel, strive to produce new thoughts and emotions? More specifically, do they consciously think about the non-conscious effects of their work – how is the suggestive created? As mentioned in the introduction of this post – if anything, the performance is suggestive, projecting a difficult-to-capture-and-convey, yet distinct, sense of the futures lost since the 1920s.

During the talk, it struck me that it may well be the rich source of influences – the abundance of ”theory” – that creates an equally rich suggestive impression. Even though most of us know little of the references drawn upon – say, 1920s excentricism in Russian acting – it may well be this exact thing that creates this sense of the performance ”doing something to me”, operating in some non-conscious register.

Here, I am not referring to the Freudian unconscious, but to the suggestive realm discussed recently in the context of Gabriel Tarde, by theorists such as Lisa Blackman. We know that most of the information that passes our minds does so in an non-conscious manner – is this what makes productions like ”The league of time” so familiar, yet unfamiliar? Remember, ”theory” can never exist ”above” or ”beyond” the everyday activities of social actors – theories coexist with ”ethnomethods”. How many of these are non-conscious? How much excentricism is there in my head, without me registering it? Uexkull talked about the fly-like character of the spider; how futurist-like and excentricism-like has my mind become, without me knowing it?